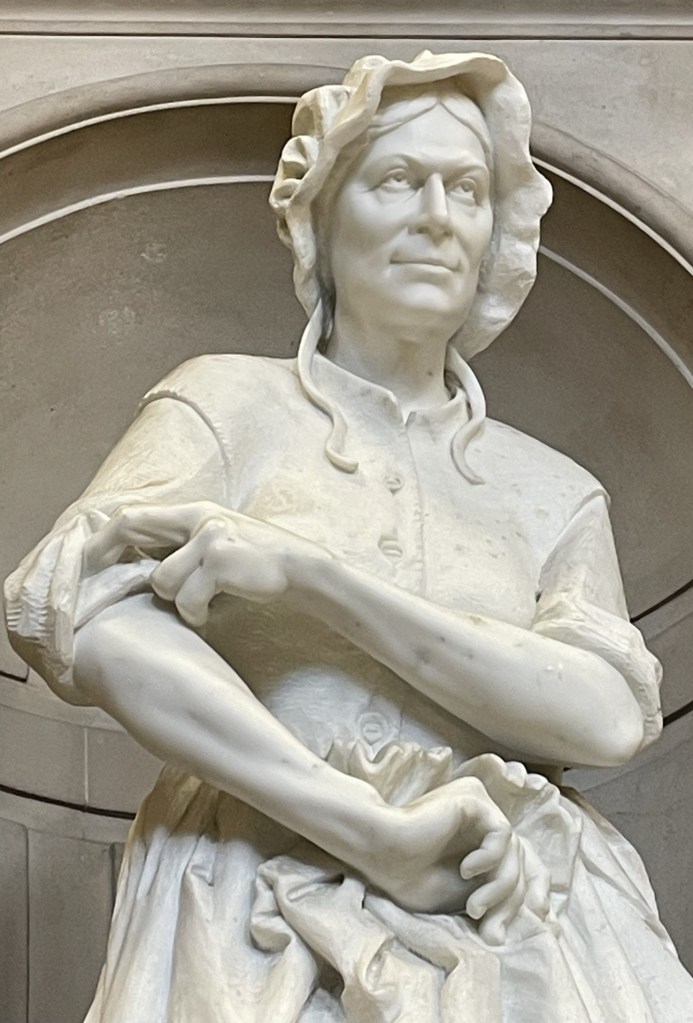

It started with an article in The Week Junior magazine heralding the unveiling of Dorset’s Mary Anning Statue. https://www.maryanningrocks.co.uk/press. A sidebar stated, ‘In the UK, there are 82 statues of men named John and just 128 of named women’.

Only 128?? I could visit all of them! But initial enthusiasm for a new project soon turned to dissatisfaction. There were so few women statues that it was, in actual fact, feasible to visit them all.

So who are the 128 immortalised women? What does it take for a woman to get a statue of herself? Money? Influence? Passion for a cause?

I’m ashamed to say I was struggling to recognise some of the names when I started the research, but that was all part of the journey – learning more about women that have played a special part in our history.

So I have given myself a year to visit all of them to give them the recognition they deserve and to learn more about these special women.

The start date is 29th July 2022. Please join me on this journey! Who knows, hopefully by the end of July 2023, the number of named women statues may be more than 128…..

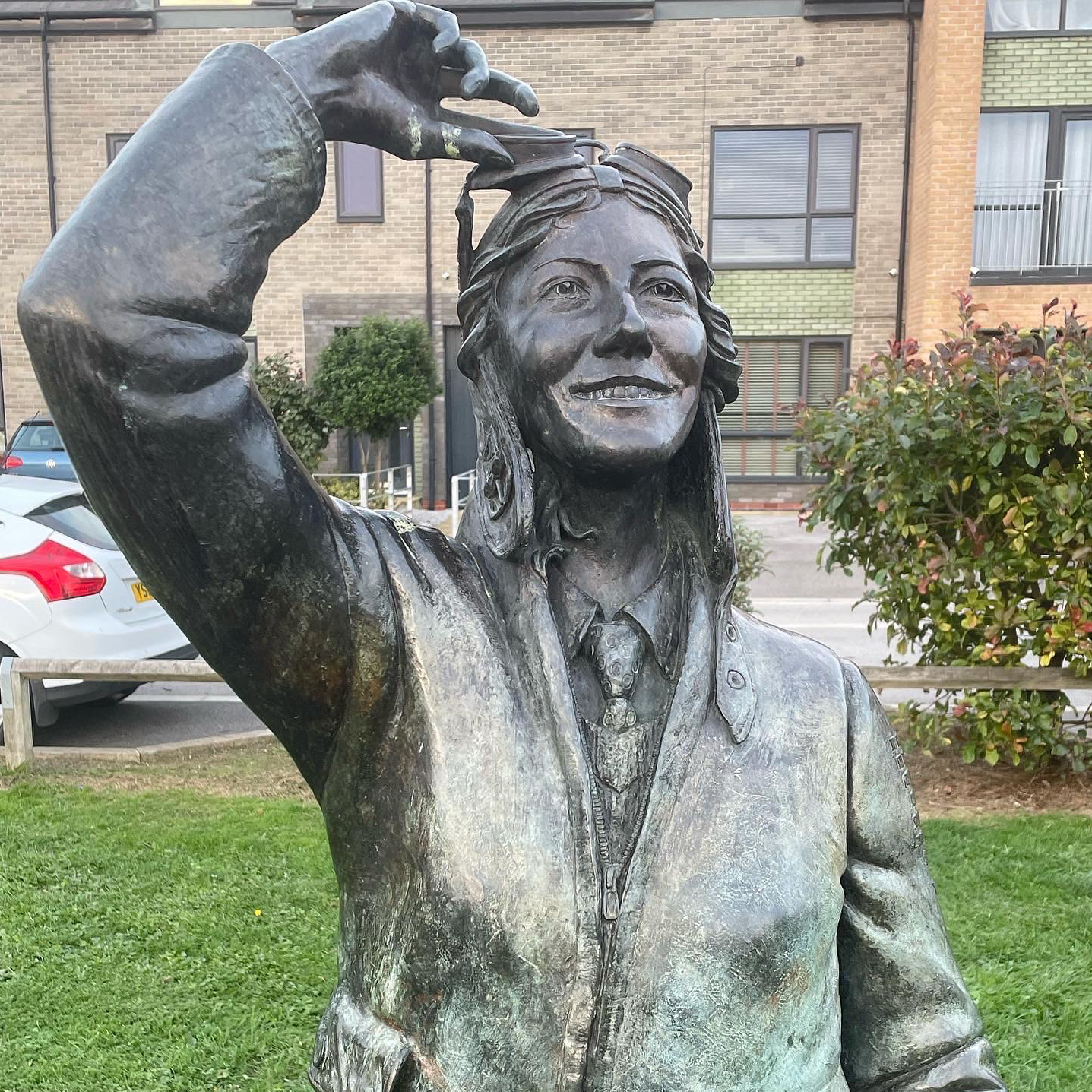

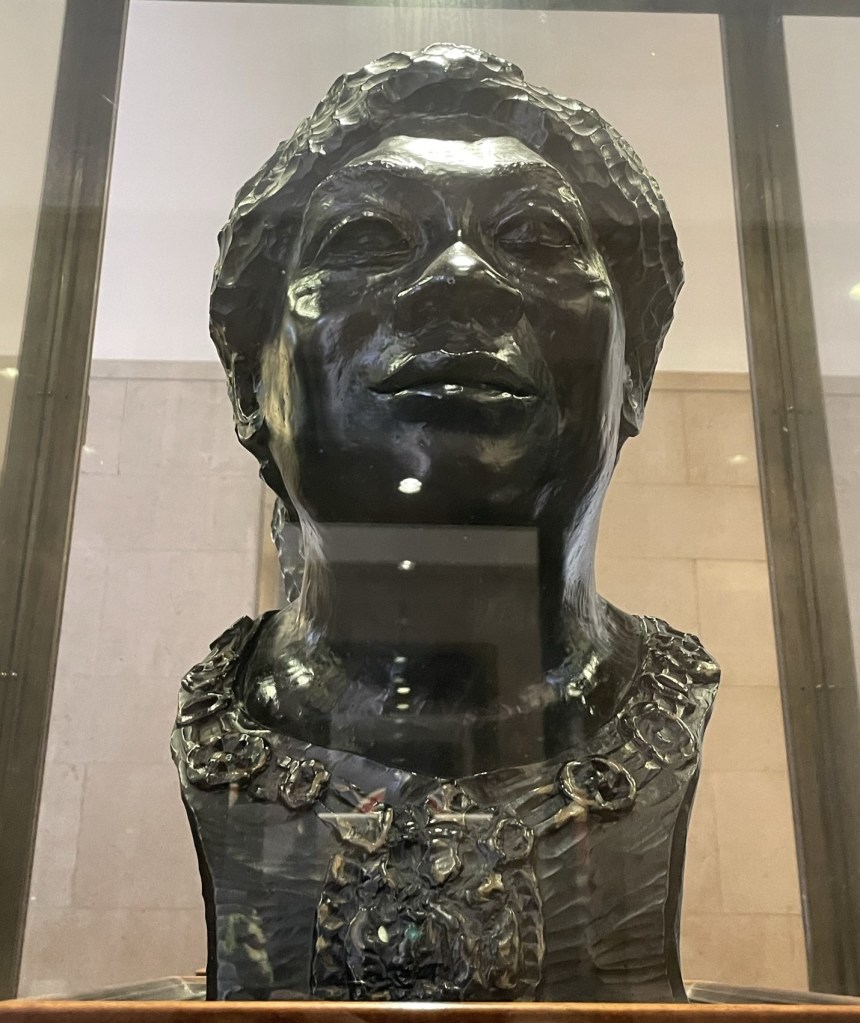

The keen eyed amongst you will know that the above picture is nothing to do with Mary Anning. It is pilot Amy Johnson who I visited in Hull. I love her gaze and besides, I’ve yet to meet Mary Anning…